EU press releases differ from their reports on Turkey

The European Commission publishes annual reports on the progress of EU candidate countries, accompanied by short press releases. I find noticeable differences between these reports and releases on Turkey; while the sentiments in the reports have been fairly stable over the years, the press releases often remarkably diverge from the reports.

The Commission’s latest report on Turkey hit the headlines as the worst EU scorecard so far.

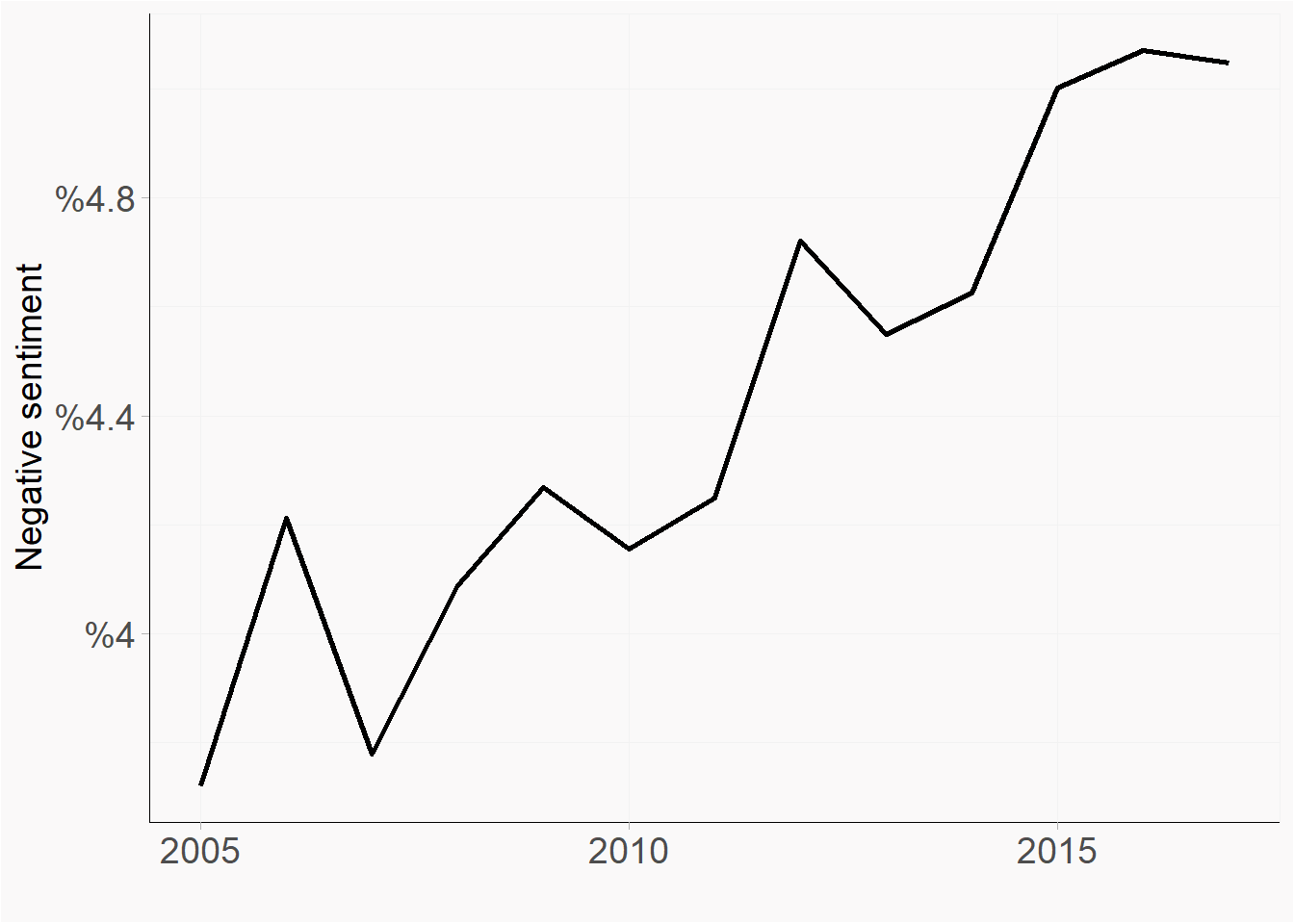

To see if there is evidence for this claim, I analysed the sentiments in the EU reports on Turkey since 2005—the year the accession negotiations started. These reports are available from the EU websites, except for 2017 when the Commission did not publish one.

To quantify the negative sentiment in the reports, I use the NRC Word-Emotion Association Lexicon, which can match words in a text with two sentiments (negative and positive) and eight emotions (anger, anticipation, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise, trust).

The figure below plots the share of words associated with negative sentiment in the EU reports on Turkey. It shows that, indeed, the 2018 report was clearly more negative than most of the previous reports. To be precise, excluding the stop words, 7.1% of the report was negative. This is only slightly behind the 2016 report, where the negativity share was 7.2%.

I think it is safe to say that these reports have very limited readership. They are not only technical, but also lengthy documents. For example. the 2018 report on Turkey is 111-page long, and the average length is about 102 pages.

This is perhaps one of the reasons why the Commission publishes press releases together with reports. These releases are much shorter; for example the latest press release on Turkey has only five pages. On average, they are about 3.5 pages long.1

Considering that press releases are more widely-read than the reports (especially by the journalists, from whom most people would learn about the reports), I wanted to compare the two types with regards to the sentiments and emotions that they reveal.

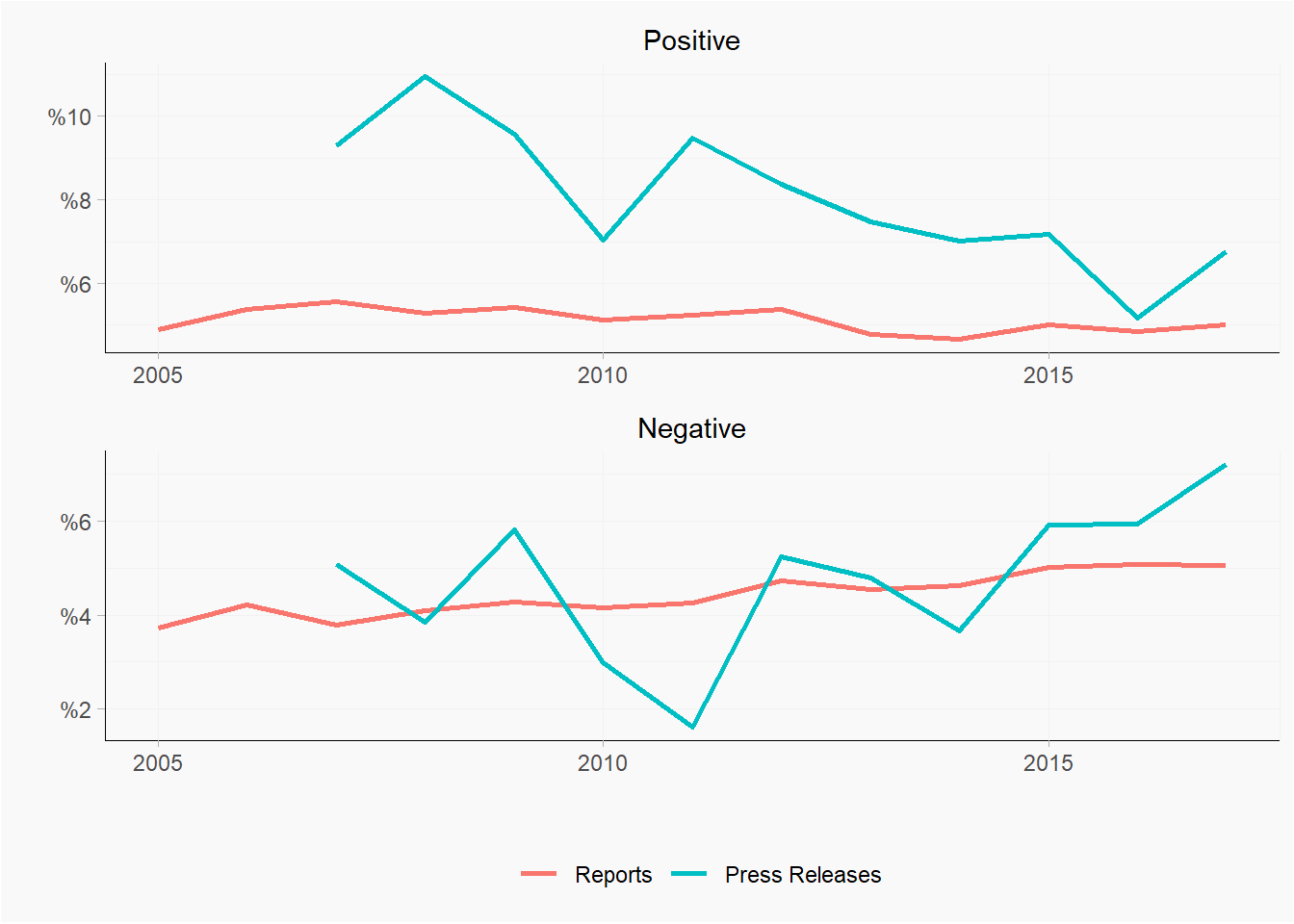

The figure below plots the results.

We see that the reports have been relatively stable over the years in almost all sentiments or emotions. This is especially true for the negative half—the categories in the bottom row. In comparison, the press releases have been ‘all over the place’.

In the upper, positive row of categories, the lines representing the releases are generally over the line for reports. In the bottom row of negative categories, the opposite is the case: the releases were below the reports until very recently.

Overall, this suggests that EU press releases have for a long time been more positive and less negative than the reports on which they were based.

This overall trend seems to have changed since 2015, at least in the negative categories. This is when the releases have become more negative than the reports themselves.

There are possibly many explanations for the difference between the reports and press releases and for the recent change in the general trend.

One such explanations could be that press releases are rather ‘political’ documents, where the Commission frames the relationship with the candidate countries somewhat independently from the bureaucratic details in the reports.

In the case of Turkey, it seems that the Commission has been brushing the negatives under the carpet and overemphasising the positives until recently, which seems to have changed with the latest press release.

Note:

- I could not find the press releases for the years 2005 and 2006 online. Therefore, my analysis of the releases are based on the data from 2007 to 2018.