Media coverage of presidential candidates in Turkey

When Dogan Media was bought by a pro-Erdogan businessman, many suspected a change in the position of its news outlets in the long-run. I compare the tweets by Hurriyet—Dogan’s top-selling daily—in two presidential elections, before and after the sale. I find unmistakable changes in the way the newspaper approached the candidates, increasing its bias towards Erdogan in the election months after the sale.

Most news media are divided into pro- and anti-Erdogan camps in Turkey. The former, larger camp is in the hands of a few conglomerates, who owe some of their wealth to their ability to win government tenders.When one of these conglomerates, Demiroren Holding, bought Dogan Media—‘Turkey’s last big independent media firm’—on 9 April, the question marks over the media freedom in Turkey just got bigger.

At the time, many commentators raised concerns about the potential effect of this sale on the media coverage of the campaign for the upcoming 2019 presidential election.

Only for Erdogan, a few weeks after the sale, to call for snap elections to be held on 24 June 2018.

Have Dogan Media news outlets changed their position towards Erdogan in the short time before the election? To answer this question, I analysed Hurriyet’s tweets1 during 50 days2 before the 2014 and 2018 presidential elections. The results show that Hurriyet was already biased towards Erdogan in 2014, which increased significantly in 2018.

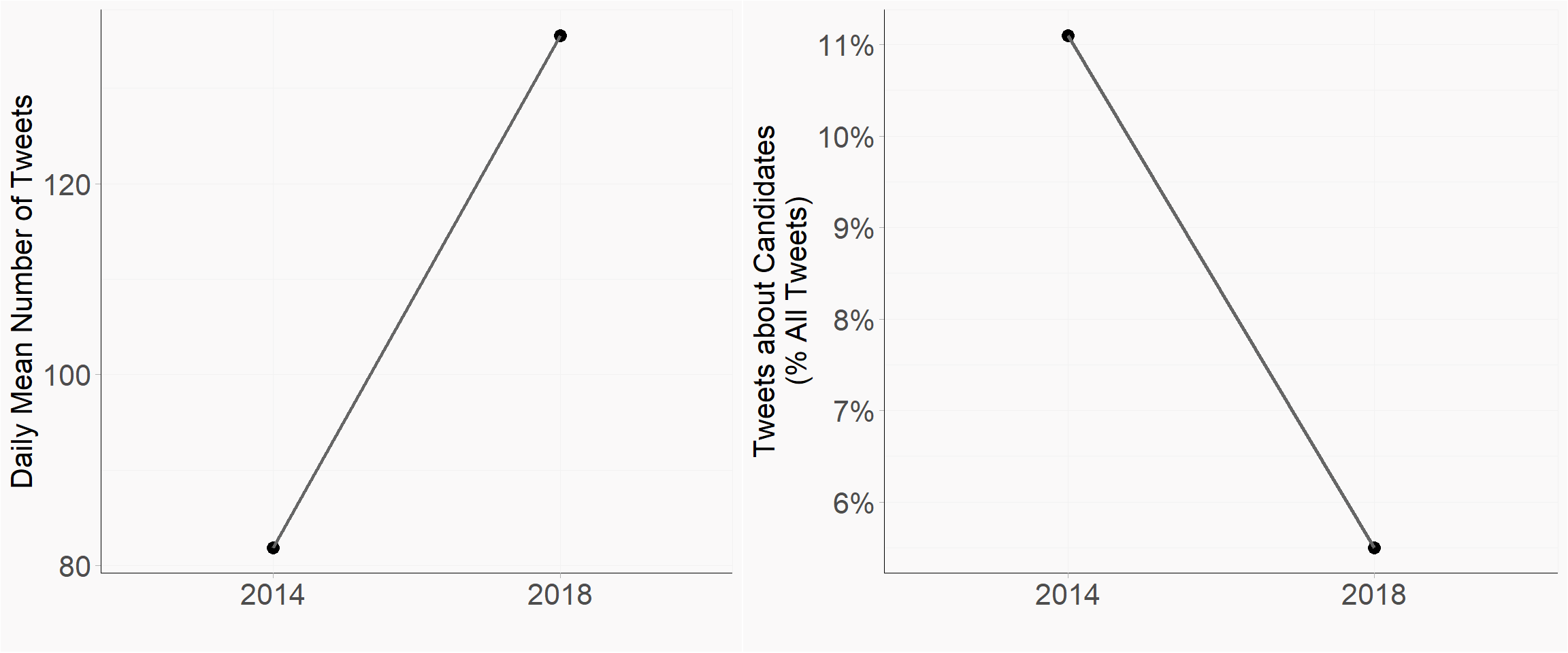

The figures below demonstrates how active Hurriyet was on Twitter during the two campaigns, and how much of this activity was related to the candidates in the campaigns.

On the left, we see that Hurriyet’s Twitter account was more active in 2018 than in 2014: while it posted on average about 80 tweets a day before the 2014 election, it now tweets about 135 times a day.

Despite this 65% increase in its overall activity on Twitter, Hurriyet’s attention to the candidates decreased—both in absolute and therefore in relative numbers. In 2014, 11% of Hurriyet’s messages on Twitter were related to the candidates in the upcoming election.3 However, the share of candidate-related tweets decreased to below 6% in 2018.

The decrease in Hurriyet’s attention to the candidates becomes all the more surprising if we consider that the 2018 election:

- was more salient due to the change from a parliamentary to a presidential system,

- was more competitive—unlike the 2014 election, there was less certainty that Erdogan would win, and

- had more candidates, and the campaign was more lively.

Overall, this suggests that Hurriyet paid relatively less attention to the election in 2018, compared with the previous election in 2014.

In a series of figures below, I will analyse how Hurriyet covered Erdogan versus all other candidates in the elections.

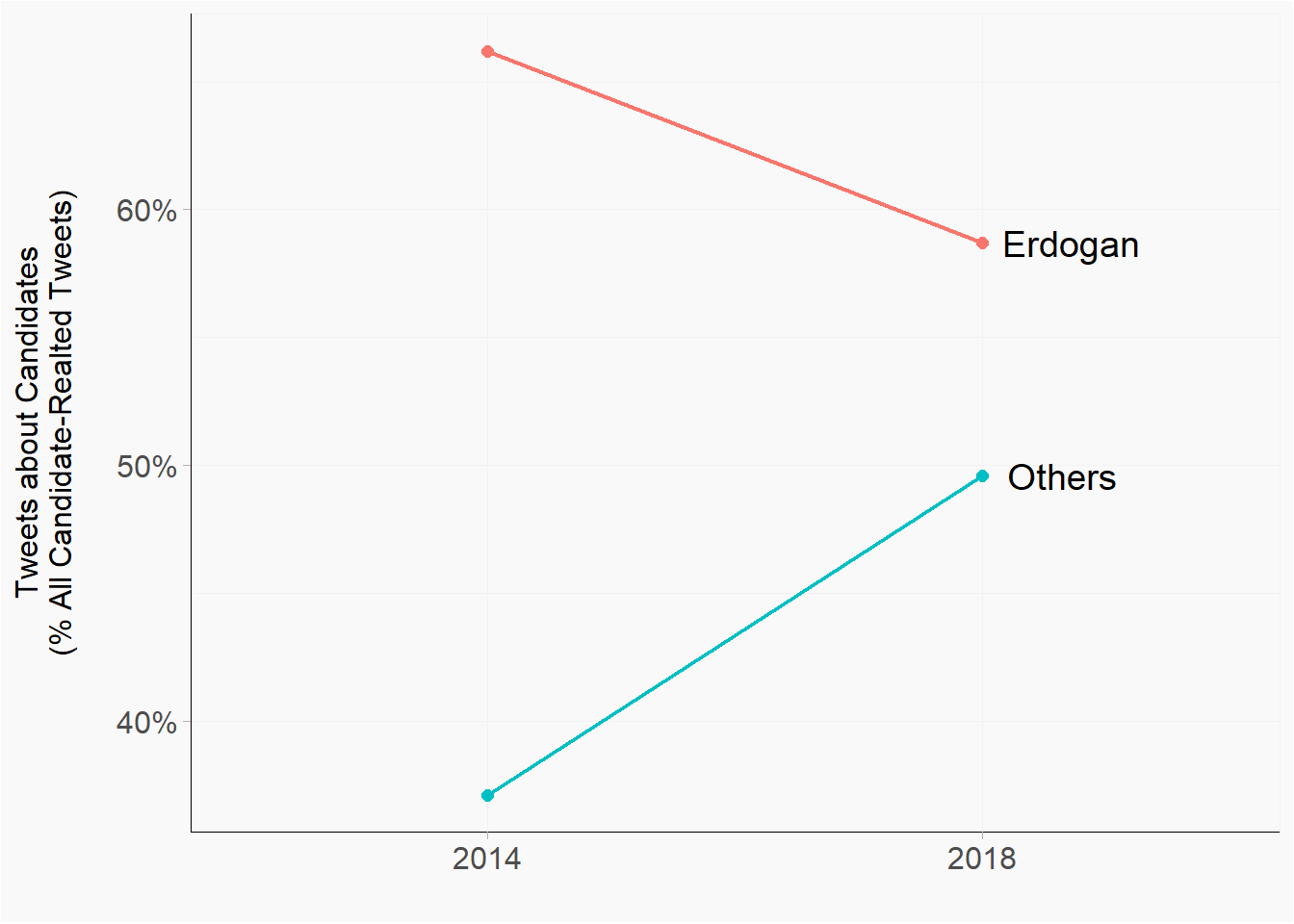

First, a general look at the share of tweets about the candidates. The figure below plots the share of messages that mention Erdogan and all other candidates anywhere in tweets.

We see that Erdogan’s share decreased while the other candidates’ share increased from 2014 to 2018. However, this figure might be misleading because it does not take the substance of the messages into account.

Consider, for example, the tweet below, where Hurriyet reports Erdogan’s call for members of parliament to sue Ince, the runner-up in the 2018 election.

Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan'dan vekillere çağrı: Bu İnce'ye dava açın https://t.co/j5MvCmafI1 pic.twitter.com/8xlVwiM5Et

— Hürriyet.com.tr (@Hurriyet) June 2, 2018

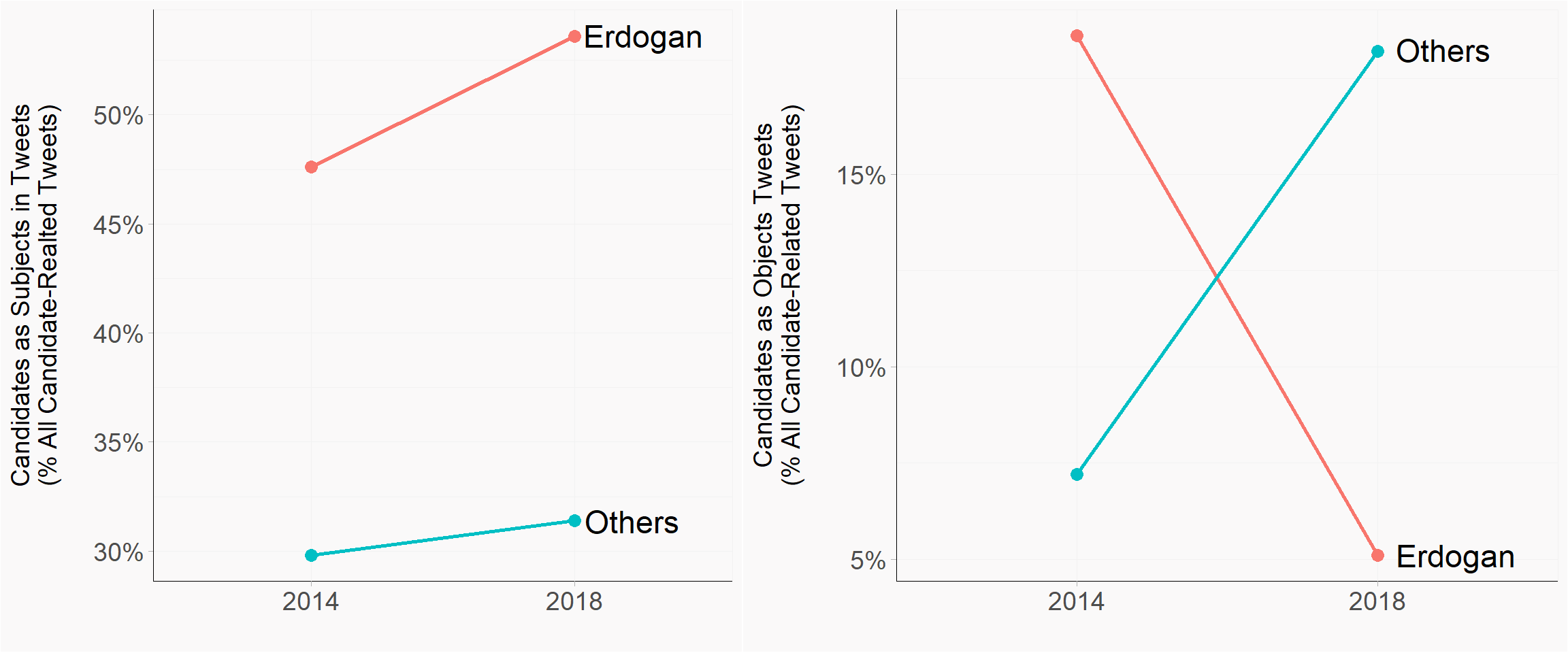

Although both Erdogan and Ince feature in this tweet, its message is clearly about Erdogan, who is the subject in the tweet while Ince is only an object. Differentiating the candidates as subjects or objects in the tweets, the figures below re-plot the data.

On the left, we see that the share of candidates as subjects increased for both Erdogan and the other candidates. However, the increase is steeper for Erdogan. This is despite the fact that Erdogan faced only two other candidates in the first election, but five in the second. Still, his share of tweets where is the subject has gone over 50%.

On the right, we see a different picture. While the share of tweets where Erdogan is an object decreased dramatically, the opposite is true for the other candidates.

These results suggests that Hurriyet gave more weight to Erdogan’s perspective in its campaign coverage of both elections, but this became more obvious in the 2018 election.

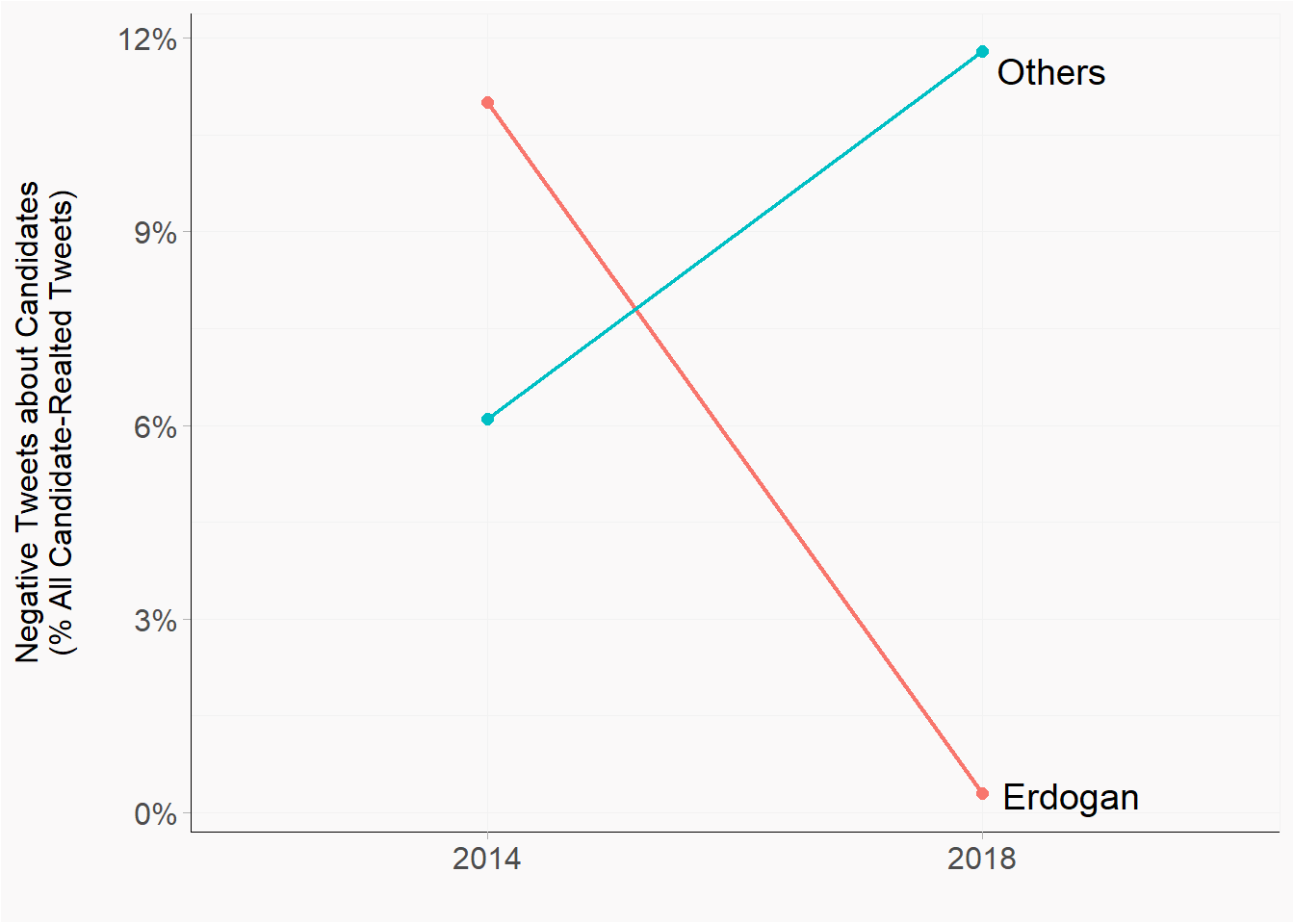

Finally, a look at the tone. The figure below plots the negative share of tweets about the candidates in two elections.

During the 50 days preceding the 2014 election, about 11% of the tweets that Hurriyet posted included something negative about Erdogan. However, there was only one single negative tweet during the 2018 campaign, and that tweet was a self-ciricitism by Erdogan, where he says he does not deny that FETO—who were allegedly behind the coup attempt in 2016—gained power during this rule.

Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan: FETÖ'nün bizim zamanımızda büyüdüğü iddiasını ben reddetmem. Bunlar büyük bir ihanet şebekesi içerisindeymiş.https://t.co/owNaR2YPqo pic.twitter.com/9AmQYHBDso

— Hürriyet.com.tr (@Hurriyet) June 7, 2018

In comparison, the negative share of all other candidates has doubled from 2014 to 2018, increasing from about 6% to 12%.

To sum up, although many thought Dogan Media outlets were independent of the government, my analysis of Hurriyet’s tweets shows that, its leading newspaper was already biased towards Erdogan during the campaign for the 2014 presidential election. However, during the most recent election under the control of a pro-government conglomerate, Hurriyet’s coverage has gone from bad to worse, and possibly from bias to propaganda.

Notes:

Analysing tweets are not only resource effective. Social media is also where more and more people follow the news, including the ones on political campaigns. At the time of writing, Hurriyet has 4.17 million followers on Twitter.

I look at only 50 days before each election because, the runner-up in the 2018 elections—Muharrem Ince—announced his candidacy 51 days before the election.

I located the candidate-related tweets by searching for the names and surnames of the candidates, and then reading these tweets to see if they were really about the elections.